What is design infringement?

Design infringement can occur when someone uses a design that is identical or similar to a registered design without obtaining permission from the owner.1 In Australia, a registered design provides designers protection for up to 10 years. Importantly, the law does not require exact copying. If the overall visual impression of the suspected infringing design is substantially similar to the registered design, it may be considered infringement.2

What do registered designs protect?

In Australia, new and distinctive designs are afforded protection with owners registering with IP Australia.3 A registered design protects the visual appearance of a product.4 The law protects visual features such as shape, configuration, pattern, or ornamentation.5 It does not protect how the product works or what it is made from.6 Designs are tied to physical products that have a tangible form.7 Products must also be manufactured or handmade and are produced on a commercial scale.8 For example, the shape of a bottle, the pattern on fabric, or the combined features of shape and patterns on furniture.

Protecting a design involves a two-part process. To gain the legal right to take action against someone who uses a design without permission, owners must first register and then certify it with IP Australia. In Australia, this two-part process to apply for a design right is crucial to enforce the right against another person. See more information here ‘How to apply for a design right’.

When it comes to design infringement, it is essential to understand what a registered design protects.

Designs are tied to specific products. Designs are registered for a particular product (like “a chair” or “a bottle”). Protection only covers the appearance of that product. If someone uses the exact design on a completely different product, this may not be infringement. For example, a chair design is used as a pattern on a t-shirt.

What is shown with the registered design is what is protected. The images and descriptions of a registered design define what is protected. Registration not only protects the design but also designs that are substantially similar. However, it does not protect every possible variation. Additionally, if a unique feature is not clearly shown or described, it may not be protected.

How does design infringement happen?

Where a design is registered and certified with IP Australia, the following combined events may constitute infringement, provided they occur during the term of protection and without the permission of the owner:

1. Someone uses the design

Australian law gives designers exclusive control over their registered designs.9 Infringement occurs when a person uses a design that closely resembles a registered design in a way that only the owner is allowed to do so and without permission.10 Someone uses a design when:

- Making or offering to make a product with the design11

- Importing a product with the design for sale or business use12

- Selling, hiring, or disposing of a product with the design13

- Using a product with the design for business purposes14

- Keeping a product with the design for sale or business use.15

2. Someone uses a design that is similar to a registered design

Infringement occurs when someone uses a design that looks too similar to a registered design. When looking at possible infringement, courts compare the registered design with the suspected infringing design.16 This comparison requires consideration of multiple factors. They consider:

- The overall look. Does the infringing design give the same overall impression as the registered design?17

- Focus on similarities between the designs. Attention is paid to what is similar than what is different.18

- What a familiar person would think. A familiar person is someone who is familiar with the product and similar products.19 They consider whether someone familiar with these types of products thinks they look too similar.

- The field for prior designs. If the registered design is more innovative and distinct from existing designs, common features between the design and the infringing design would support a finding of infringement. On the other hand, if the registered design is only slightly different from existing designs, small differences between the registered design and the infringing design support a finding of no infringement.20

- Common features. Features that are common in many similar products are given less importance.21

- Design options. Courts will consider how many different ways a designer could create a design for the product.22

- Statement of Newness and Distinctiveness. A registered design can include a statement that highlights the new and distinctive aspects of a design, helping to focus protection on crucial elements. Comparisons between designs will then focus on these features.23

Examples of design infringement

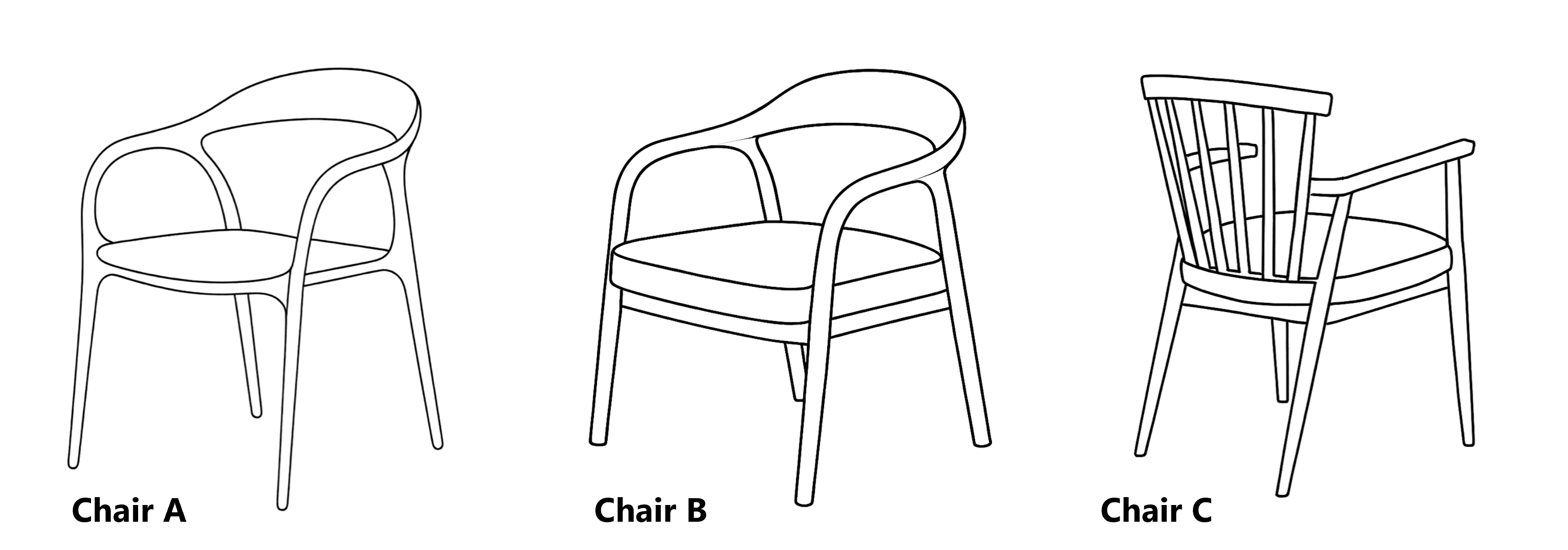

For example, a furniture company registers a design for a distinctive chair (Chair A) with a unique curved backrest and armrests that flow into the seat in one continuous line.

Might be an infringement: Another company makes a chair (Chair B) with the same flowing lines from armrests to seat, differing only in size and materials.

Probably not infringement: Another company makes a chair (Chair C) with a similar seat but completely different backrest and arms.

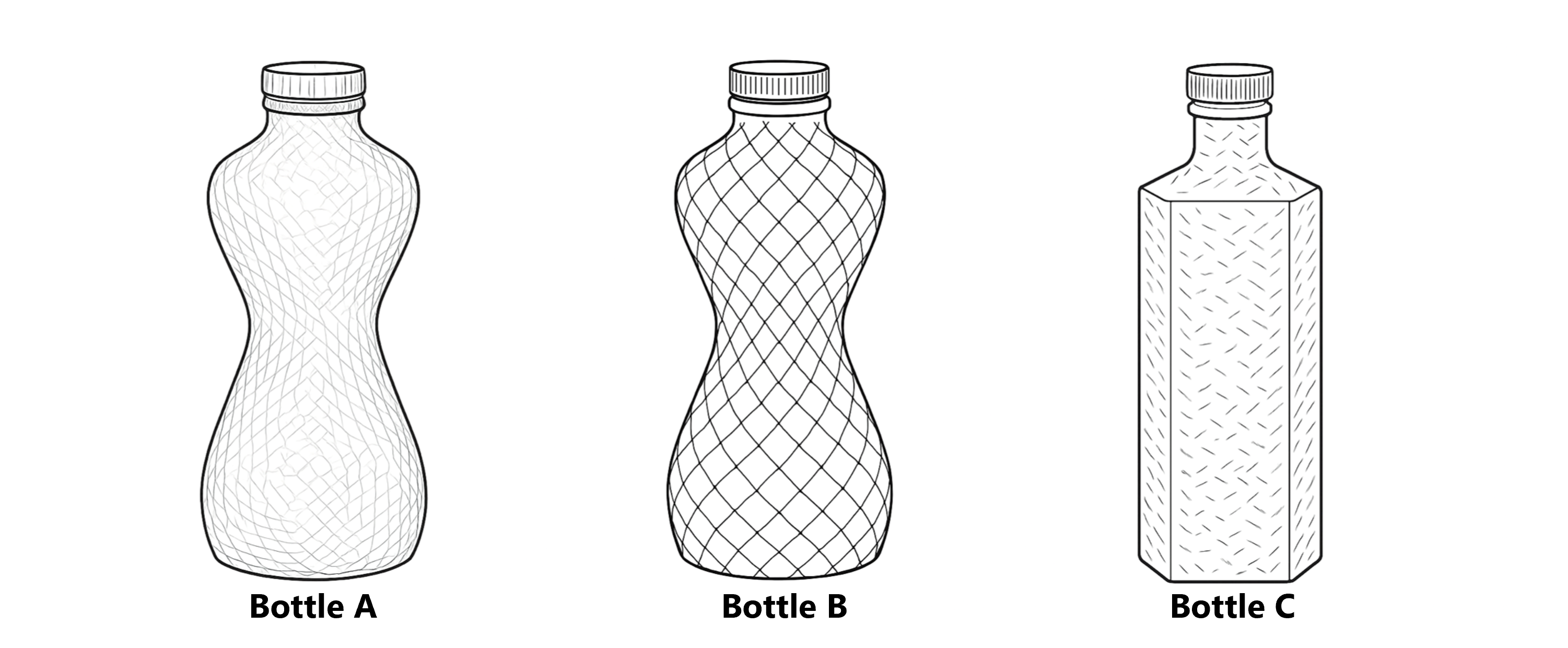

For example, a soft drink company registers a design for a bottle (Bottle A) with a distinctive hourglass shape and textured surface.

Might be infringement: A competitor makes a bottle (Bottle B) with a very similar hourglass shape and a slightly different but recognisably similar texture.

Probably not infringement: A competitor makes a bottle (Bottle C) with a completely different shape but uses a texture that is somewhat similar.

What is not design infringement

It is important to understand what does not constitute infringement. The Designs Act 2003 provides several situations where a registered design is not infringed, including:

- Prior use defence. If the suspected infringing design was already being used in Australia before the registered design, the design may continue to be used.24

- Repairs and spare parts: In certain circumstances, using a design to repair a complex product may not be infringement.25 This defence recognises the practical need for replacement parts.

Navigating design infringement can be complex and often requires legal expertise. The scope of protection, the similarity between designs and available defences can all affect the outcome. Additionally, for infringement to occur, the registered design must be legally valid. Registered designs can be re-examined by IP Australia or challenged in court if, for example, it is not new or distinctive. An expert can help navigate these issues and provide advice. This guide provides a starting point, but qualified professionals should assess specific cases.

- Designs Act 2003 (Cth) s 71 (‘2003 Act’).

- Ibid s 71(3).

- Ibid s 15.

- Ibid s 5 (definition of “design”).

- Ibid s 7.

- Ibid s 7(3).

- Ibid s 6.

- Ibid.

- Ibid s 10.

- Ibid s 71(1).

- Ibid 71(1)(a).

- Ibid s 71(1)(b).

- Ibid s 71(1)(c).

- Ibid s 71(1)(d)

- Ibid s 71 (1)(e)

- GME Ptd Ltd v Uniden Australia Pty Ltd (2022) 166 IPR 551.

- 2003 Act (no 1) s 19(1).

- Ibid s 19(1).

- Ibid s 19(4).

- Keller v LED Technologies Pty Ltd (2010) 185 FCR 449, [46] (Emmett J).

- Ibid s 19(2)(a).

- Ibid s 19(2)(d).

- Ibid s 19(2)(b).

- Ibid s 71A.

- Ibid s 72.